“Japanese First” and the Race to the Bottom: How Japan’s Upper House Election Became a Showcase for Xenophobia

In this Japan's Upper House elections, rightwing parties are locked in a competition that feels eerily familiar to anyone who’s watched American politics, with even "a Japanese Trump" in the running.

Originally published July 17th, Updated July 21st 2025. Update at the bottom

In this year’s upper house elections, Japan’s conservative parties are locked in a competition that feels eerily familiar to anyone who’s watched American politics over the past decade. Each party seems determined to outdo the others in channeling Donald Trump’s brand of populist, xenophobic rhetoric. The dog whistles have become foghorns; some candidates are skipping the coded language and saying the quiet part out loud. With foreigners making up less than 3% of Japan’s population, the catchy phrase “Japanese First” has turned this tiny minority into a convenient scapegoat for the country’s persistent social and economic woes.

The New Populist Playbook: “Japanese First”

The Sanseito party (参政党) has surged in popularity by waving the “Japanese First” banner and railing against what it calls “excessive acceptance of foreigners.” Their message, amplified by social media, has forced even the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to take a harder line, pledging to “accelerate efforts toward zero illegal foreigners.” The ruling parties are clamoring to make it more difficult for non-Japanese to naturalize and easier to revoke permanent residency for those who call Japan home. Other parties are racing to keep up: the Democratic Party for the People wants to clamp down on foreign real estate investment, while the Japan Innovation Party is calling for an overall cap on the number of foreigners allowed into the country. The contest is not about who has the best solutions for Japan’s problems, but who can be the most restrictive, the most suspicious, and the most exclusionary.

From Dog Whistles to Megaphones

What’s especially alarming is how openly xenophobic some candidates have become. At campaign rallies, Sanseito leader Sohei Kamiya has made sweeping, disparaging claims about foreigners and crime. Kamiya, to everyone's astonishment, held a surprise press conference at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan the day before elections began on July 3rd. Kamiya spoke with foreign correspondents, defending a tough stance on immigration and linking migrant behavior to “exploiting loopholes and committing crimes.” He framed it as national security, not cultural bias. He claims not to be racist but has a vision of Japan where foreigners are treated like labor in Singapore and Dubai–disposable part-time workers. He did also suggest they should be treated better during their time in Japan so they don't turn into criminals.

He and his party blamed the pandemic, "dubious vaccines" and much of Japan's woes on "Jewish capital" but when I pressed him for a definition of the term, he politely backtracked and declared he was not antisemitic. Kamiya says, "I have Jewish friends and in fact, was a member of the Japan-Israel Friendship Society which led online commentators to accuse me of being a puppet of the Jews." Despite a history of putting his foot in his mouth, Kamiya is charismatic and has been leading his party in becoming a real presence on social media, and possibly in the upper house.

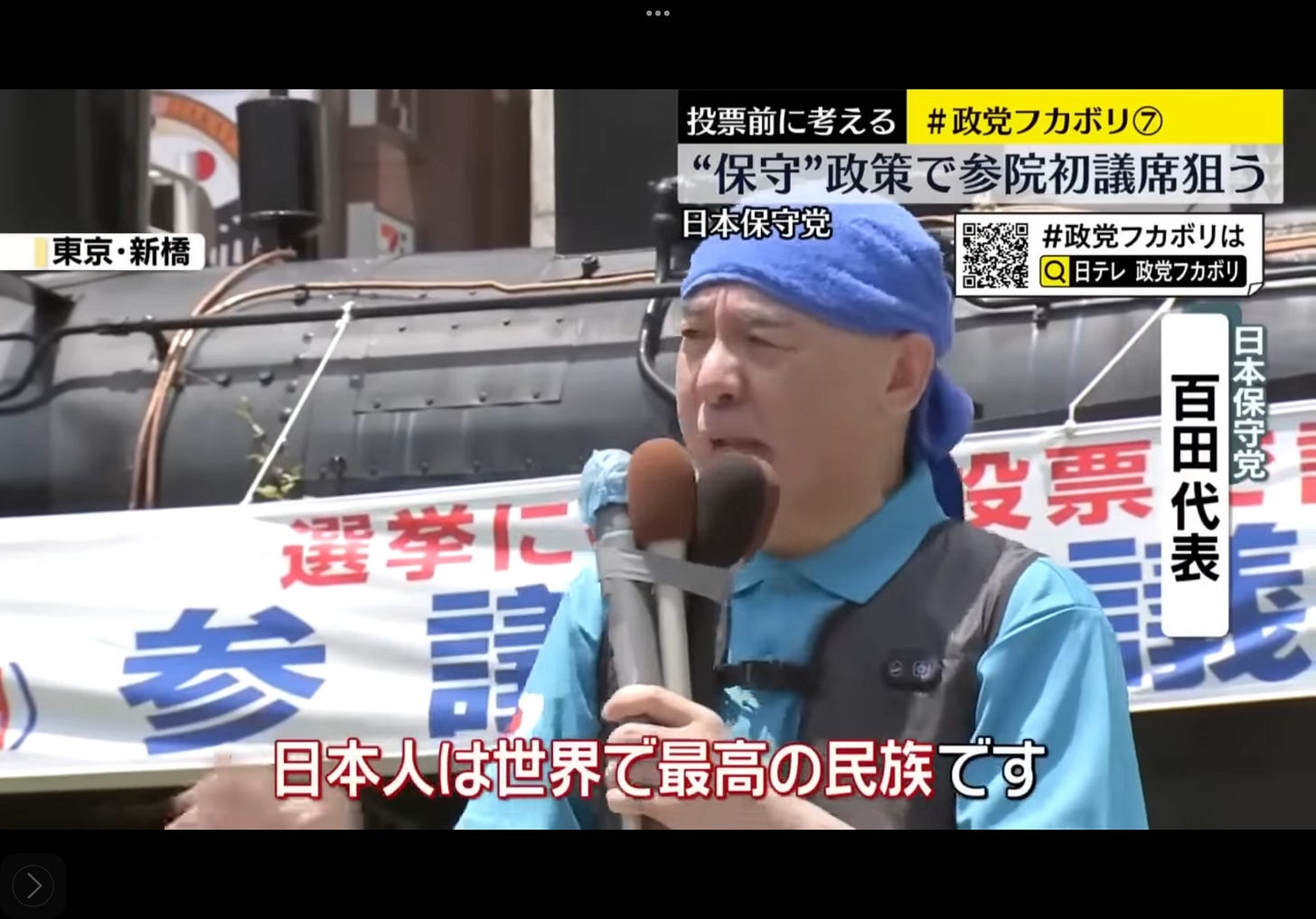

Nippon Conservative Party leader Naoki Hyakuta paints foreign workers as cultural threats and criminals, warning that they will destroy Japanese society. He declares, "The Japanese are the greatest ethnic group (民族/minzoku) on earth.” Hyakuta is a novelist well-known for his whitewashing of the kamikaze pilots in the historical novel, Eternal Zero; the novel was much beloved by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Naoki-kun is also infamous for tweeting about his ability to masturbate many times in a single day like a young man.

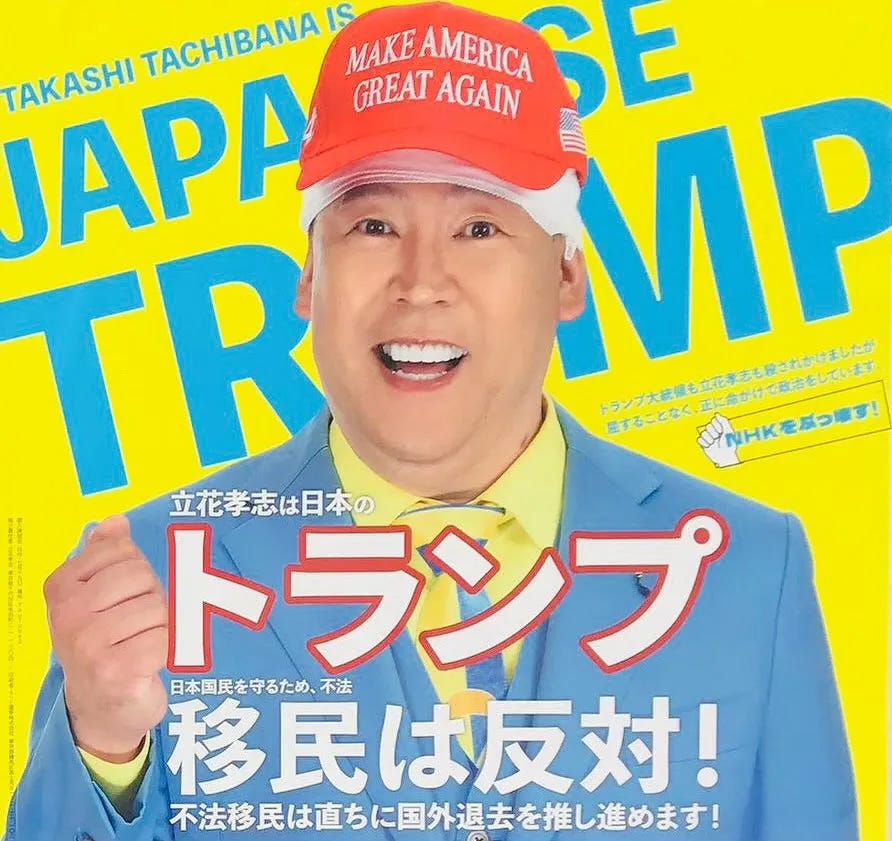

NHK Party leader Takashi Tachibana dispenses with any pretense, declaring, “I will continue to be racist because I’m scared,” and openly expressing fear of black and Muslim people. These are not fringe voices—they are party leaders, and their words are being broadcast to millions. Tachibana is the most slavish sycophant of Trumpism. He has a political party declaring that he is "the Japanese Trump."

On a sweltering July afternoon in Kobe, Tachibana—also founder of the NHK Party, provocateur, and Japan’s budget-brand Steve Bannon—took the stage with no sash, just a red baseball MAGA cap.

Tachibana isn’t running to win over the undecided. He’s here to shake the tree, shout down the media, and rail against foreigners—especially the undocumented ones. “If we keep talking sweet, we’ll be invaded,” he warned. “Illegal immigrants? Kick ’em out.” The rhetoric was familiar, but the delivery had a uniquely unhinged local flavor.

Like his idol Donald Trump, Tachibana sees himself as a martyr for the people. Trump allegedly took a bullet to the ear. Tachibana? Back in March, he was attacked with a nata—a Japanese machete—by a disgruntled man outside his Tokyo office. The blade slashed near his left ear. He survived, posted photos online, and turned the incident into a campaign talking point.

“You see? Politics in Japan is life and death,” he told the crowd. “Just like Trump, I’m fighting with my life on the line.”

Tachibana’s performance wasn’t about policy. It was a theater performance. A man on a mission to stay relevant by swinging wildly at immigrants, journalists, and decorum. And if that doesn’t win him votes, it’ll at least keep the cameras rolling.

This wave of hate speech has not gone unchallenged. Amnesty International Japan and a coalition of 266 organizations have issued urgent statements condemning the scapegoating of foreigners. Groups like the Anti-Poverty Network have reminded the public that Japan’s deep-seated social problems are not the fault of immigrants, and have called for politics based on universal human rights, not division and fear. Yet, the sheer volume of hate-filled rhetoric has made it difficult for fact-checkers and activists to keep up.

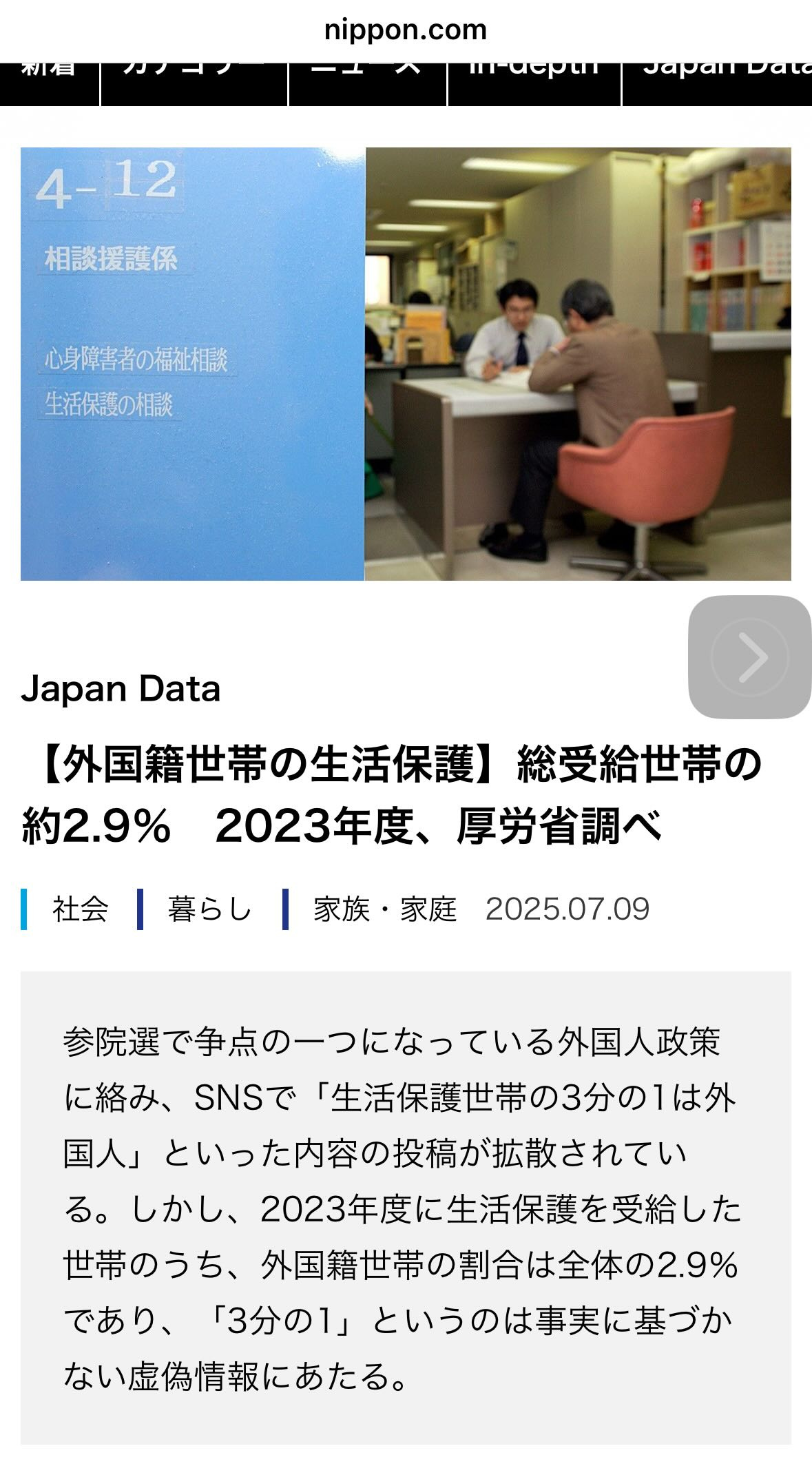

“They’re eating the cats and dogs! And taking all the welfare money!”

One thing that poured gasoline on smoldering feelings of resentment towards the foreign population is a terrible lie that foreign residents account for 33% of those on welfare in Japan—-yes, the familiar, “free-loading immigrants” fib. According to some excellent reporting by the Mainichi Newspaper, devious claims circulating on social media since March falsely assert that foreign residents make up one-third of all welfare recipients in Japan. These posts, which went viral just before the Upper House election campaign began, misused data by comparing the monthly total of all welfare households (about 1.65 million) with the cumulative annual total of foreign-headed households (about 560,000), leading to the bogus 33% figure. In reality, foreign residents account for only about 2.9% of welfare according to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The misinformation spread widely due to an early article on nippon.com that failed to clearly note the numbers represented annual totals; the site later added a correction and deleted the misleading content. But the data was soon spread all over social media, unchecked. Nippon.com published a corrective article but has really failed to take responsibility for the havoc they unleashed. One could argue they have a civic duty to do so.

In their July 9th article, Nippon.com notes, Amid foreigner-related policies becoming one of the focal points of the Upper House election, posts have been spreading on social media claiming that "one-third of welfare recipients are foreigners." However, in fiscal year 2023, households with foreign nationality accounted for only 2.9% of all households receiving welfare. The claim that "one-third" are foreigners is false and not based on fact,

The Danger of Division

Journalists and commentators warn that unchecked hate speech and emotional arguments only fuel the rise of the far right. If those who oppose xenophobia respond only with emotion, they risk playing into the hands of extremists who thrive on outrage and division. The result? An ever more polarized society, with minorities caught in the crossfire.

Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike stepped up to the microphone on July 11 for her regular press conference and delivered what some might mistake for a moment of conscience. “It’s very dangerous,” she said, “when hate speech becomes a competition and leads to exclusionary policies.” She was referring to the way immigration policy had become a centerpiece of this summer’s Upper House election campaigns. “I want to see a discussion on how we can coexist.”

Touching words, if you don’t look too closely.

The governor then pivoted—without missing a beat—to the usual refrain: foreigners and crime, foreigners and trash, foreigners and the creeping sense of urban decay. “I think many people are worried when they hear about crimes by foreigners or see how they dispose of garbage,” she said, like someone softening a complaint to the manager about the neighbors upstairs. Koike added that the Tokyo Metropolitan Government would continue to “properly convey the rules of Japan and Tokyo.”

Ah yes, the rules. Rules like: don’t make too much noise, separate your recyclables, and never, ever mention the Koreans slaughtered after 1923 Kanto Earthquake—unless it’s to deny it happened. Which is exactly what Koike has done, year after year, by refusing to acknowledge the massacre of Korean residents carried out by vigilantes and authorities alike while the city burned. A denial made louder by silence, every September, when she skips the memorial and offers no condolence.

You might think a politician so attuned to Tokyo’s global image—so invested in making the city palatable to tourists and international investors—would think twice about alienating anyone. But Koike’s concern seems to end where Koreans begin. Especially Zainichi Koreans, Japan’s long-term ethnic Korean residents, who exist in that uncomfortable space between neighbor and nonentity. Her past associations with far-right groups and refusal to distance herself from anti-Korean rhetoric have not gone unnoticed.

So when Koike talks about the “dangers of exclusion,” it’s worth asking: who’s being excluded from her definition of coexistence? And who, exactly, does she think should be making the rules?

In Tokyo politics, as in crime fiction, you have to pay attention to what’s not being said. And Koike’s silences speak volumes.

Will Japan Follow America’s Path or Return to 1919 and Push for Racial Equality?

Japan’s current political climate is a warning sign. The country risks alienating not just its tiny foreign population, but also the tourists and international partners it depends on. If Japan continues down this path, emulating the worst of America’s recent political trends, it may find itself not only more divided but also less welcoming to the world. That would be a loss for everyone.

Japan has always had an undercurrent of hardline xenophobia which politicians have exploited to gain power yet at the same time, there has also been a large strata of society that advocates tolerance and even racial equality. Last year, I attended Washington Post columnist Karen Attiah's class on Race, Media and International Affairs 101 at Columbia University. I was surprised to learn that in the spring of 1919, Japan made a huge stand against racism. As the victors of the Great War gathered in Paris to draw new lines and write lofty promises, Japan came to the table with a simple ask: a clause in the Covenant of the League of Nations affirming racial equality. Nothing radical—just that all member nations treat foreign nationals the same, no matter the color of their skin or the sound of their names. France, Italy, and Greece gave polite nods. Australia recoiled, worried the whole thing might unravel their precious White Australia Policy. Britain and the United States, not eager to rock their own segregationist boats, fell in line behind the no.

Woodrow Wilson, wearing the halo of high-minded idealism and the scowl of a man who hated being contradicted, chaired the League Commission. When the vote tilted in Japan’s favor, he slid in a poison pill—declaring the measure needed unanimous consent. Just like that, the clause was dead.

Japan walked away feeling betrayed, humiliated. The West had spoken, and the message was clear: you’re good enough to fight beside us, but not to sit beside us. The sting would fester, and in time, it would reshape Japan’s place in the world.

And Woodrow Wilson? History remembers him as a visionary. But the closer you look, the clearer it gets: he was just Donald Trump with glasses.

As Japan’s upper house election heats up, conservative parties are racing to be the most xenophobic, using foreigners as scapegoats for the country’s problems. Civil society is pushing back, but the danger of deepening division is real. Japan must decide whether to follow the path of fear and exclusion, or to embrace a more inclusive and compassionate approach to its challenges.

UPDATE:

For three years, Sanseito was a political footnote—just one seat in Japan’s 248-member upper house, a single voice lost in the murmur of parliamentary formality. But that was before Sunday’s election. Now they’ve got 14 seats and headlines to match, and Japan’s political establishment is doing a slow double take.

The party came into being in 2020, born of the pandemic and nourished on doubt. While the rest of the country masked up and tuned out, Sanseito found its voice on YouTube—talking vaccines, government overreach, and whatever flavor of conspiracy would draw eyes and clicks. It worked. People were scared. Sanseito gave that fear a name, then gave it something to vote for.

These days, they’ve repackaged the message. Less pharma panic, more flag-waving. The new gospel is “Japanese First” (日本優先), a catchy little phrase with an edge sharp enough to draw blood. Foreigners, they warn, are slipping in under the radar. Not with armies or warships, but silently. Like mold. Like termites. A “silent invasion,” they call it, and the message lands best on places like 5ch and the darker alleys of Twitter.

Sanseito didn’t just find its audience—they built it, feeding it a steady diet of lost identity and vanishing purity. With Japan’s borders open again and tourists pouring in like floodwater, the message started to stick. Even the ruling LDP, which has made a career out of cautious nationalism, seemed rattled enough to throw together a committee on immigration and tourism reform—just in time to look responsive, just too late to look sincere.

So now the analysts are weighing in, some seeing a populist wave swelling beneath the surface, others calling it a protest vote with a half-life. NHK, Sankei, even Nikkei—they’re all running the numbers and checking the wind. But behind the data points and pie charts is something older, something raw. People are uneasy. About change. About who gets to call the country home. About what happens when tradition turns into tourism brochures.

Sanseito says it’s just getting started. Whether that’s true—or whether the party burns hot and fades fast—depends on whether fear proves more durable than facts. For now, the seat count tells one story. The streets and the screens may tell another.

Individuals Making Xenophobic and Hate Speech Statements in the Upper House Election

Sohei Kamiya (Sanseito Party Leader)Role: Leader of the Sanseito party.

Statements: Publicly claimed that globalization is the "cause of Japan's poverty" and has repeatedly warned of a "silent invasion" by foreigners. He has also made disparaging comments about foreign investment, “Jewish capital” and the influence of non-Japanese residents, using the slogan “Japanese First” in campaign speeches.

Naoki Hyakuta (Conservative Party of Japan Leader)

Role: Leader of the Conservative Party of Japan, novelist and TV commentator.

Statements: Asserted that foreign workers "disrespect Japanese culture, ignore the rules, assault Japanese people, and steal their belongings." He has also objected to foreign burial customs and insisted that foreigners must adhere strictly to Japanese customs and etiquette

.

Takashi Tachibana (Leader of the NHK Party

Role: Leader of the NHK Party (The Party to Protect the People from NHK).

Statements: Declared in campaign speeches that he would "continue to be racist because I’m scared," and expressed fear of black and Muslim people gathering in public places. He has also made statements suggesting that discrimination and bullying are part of "divine providence," and has even alluded to genocide as a solution to overpopulation in video content.

These individuals, as party leaders, have made highly publicized xenophobic and discriminatory remarks during the current Upper House election campaign, contributing to the rise of exclusionary rhetoric in Japanese politics.

I was wondering why they chose the slogan “Japanese (people) first” rather than “Japan (nation) first” like trump’s America (nation) first. The Japanese version I think is much more sinister where they intend to bully the minority inside Japan and normalize racism. Trump’s slogan is partly xenophobic but its intention is structured towards fighting foreign nations like China rather than every minority inside of the country. A slight difference in phrase but it causes far more damage to innocent people whose only crime is their different background and ethnicity. Foreigners in Japan already face severe racism daily by being rejected from renting apartments because of their nationality, being underpaid or not being paid at all by employers, and more. Japan was already “Japanese first”. I don’t know how much more they can make it “Japanese first”.

So you slander people, falsely accuse them of domestic abuse then run off like the coward you are?

Japan isn’t a big country, I hope to run into one day. My advice? Stay in Tokyo you rat.